alternative drug policies

There is a wide range of policy options for controlling the supply and distribution of drugs, from prohibition to free-market legalization. Each involves decisions and restrictions that shape not only the market but also the resulting health and social problems. While Canada can look to other countries for lessons in drug policy reform (e.g. Portugal for decriminalization), Canadian policy must reflect our own values and objectives, which strongly suggest policies that support public health and human rights.

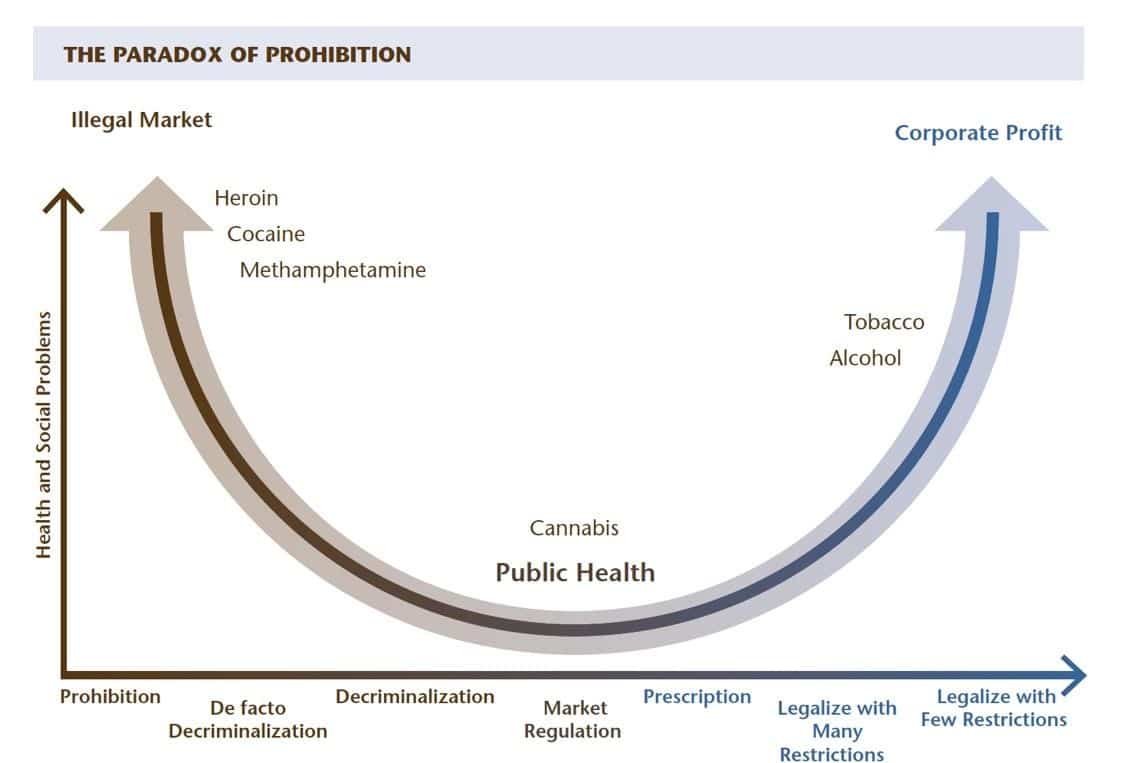

The diagram below shows the range of drug policy options and the levels of health and social problems associated with each. Cannabis for non-medical uses, as of October 2018, has moved down the curve from the left where it was previously illegal. It is now closer to the middle and bottom of the curve, where market regulation is informed by public health principles.

Decriminalization

Decriminalization removes criminal penalties for certain activities involving drugs. In most examples of decriminalization, the substances are still illegal to produce and distribute, but people caught possessing or consuming them will not go to jail or get a criminal record. Instead, penalties (if imposed) are administrative, such as fines.

As Canada is in the middle of its worst overdose crisis in history, we are now hearing calls for decriminalization from politicians, health professionals, advocates, and the media. The idea is not new. Some countries have had decriminalization in place since the 1970s, while others never criminalized drug use and possession in the first place. Currently, there are about 30 countries that have adopted formal policies of decriminalization, from the Czech Republic to Mexico, to some jurisdictions in the United States.

In 2001, Portugal decriminalized drug possession with very successful outcomes including consistently low drug use rates; an increase in the number of people in drug treatment; reduced HIV diagnosis; and reduced overdose fatalities, arrest, and incarceration of people for drug offences. In a joint position, 31 United Nations agencies have supported the decriminalization of possession and use.

Some of the documented benefits of decriminalization include

- Cost savings by reducing court and prison expenses and freeing up law enforcement resources

- Prioritization of health and safety over punishment for people who use drugs

- Reduction of stigma associated with drug use, encouraging those with substance use disorder to seek treatment and support

- Removal of barriers to evidence-based harm reduction practices, such as drug checking, opioid-assisted therapy, and needle-syringe programs

Decriminalization could take many forms. De jure (legal) changes in Canada would mean that penalties outlined in the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (CDSA) would be removed by the federal government for some drug offences, including possession. De facto (in practice) changes could be done on a provincial or municipal level by directing police to de-prioritize drug offences, as was recently recommended by British Columbia’s provincial health officer.

Although simply removing criminal penalties for possession and small-scale distribution would have immediate beneficial effects, some jurisdictions decriminalize while also scaling up health services, putting in place non-criminal (administrative) penalties for drug infractions.

Legalization

Legalization—or legal regulation—is a policy approach where the government manages the production and supply of substances instead of an unregulated illegal market without quality and safety controls. In other words, the drugs themselves become legal and the government ensures they are safe. While decriminalization has important public health and human rights benefits, it still leaves the production and distribution of drugs to an illegal market where the supply chain can be contaminated at any number of points. That is one important difference between legal regulation and decriminalization: legal regulation sets up a system of control that produces safer drugs through the creation and enforcement of rules for production and distribution.

In October 2018, Canada became the second country to legalize cannabis. In the Canadian system of legalization, the federal government sets standards for production, packaging, types, and strength of products that can be produced, as well as baseline rules. It also licenses producers of cannabis. Provinces and territories set rules for the distribution and sale of cannabis and can craft stricter regulations about things like the age of access and quantity purchased. They also license distributors and retailers. Notably, Canada did not completely decriminalize cannabis use and possession, but rather, created new penalties for those acting outside the legal system.

When enacting the new Cannabis Act, the federal government highlighted three main goals of legalization:

- Keep cannabis out of the hands of youth

- Keep profits out of the pockets of criminals

- Protect public health and safety by allowing adults access to legal cannabis

Legal regulation sets standards about many aspects of producing and selling safe products for consumers, including pricing, packaging, marketing, and quality. To reduce the harms to people consuming drugs, we would want to ensure rules around

- Who gets access to what drugs

- How access is granted

- How much of a drug can be accessed

- Where drugs can be consumed

- What kinds of health and safety information is provided alongside the drug

Is legal regulation of other drugs a good idea? It depends. Opening up a commercially driven, for-profit market for drugs that carry substantial health and safety risks could swap one set of problems for another. Consider alcohol, for example, where loose, profit-focused regulations have led to serious public health and safety outcomes like drunk driving, dependence, and violence.

On the other hand, we know that the existing system of prohibition fuels organized crime, an illegal market that is increasingly contaminated with deadly chemicals and unacceptable overdose deaths. If we regulated using a public health and human rights approach, could we reduce the negative effects of prohibition while minimizing the risks to individuals and society? Alongside any legal model, we’d certainly want to see lots of education and training about substances, harm reduction, and scaled-up access to services like drug treatment for those who need it.

The legalization of substances may seem like a radical idea but remember that our current system of prohibition has only been in place for about 100 years. Before that, substances were widely available, but not necessarily from within a public health framework. Over the past century, while we were ratcheting up drug control, we were also developing more sophisticated ideas about public health, human rights, and social justice. Creating a new system based on these principles could reduce the harms of prohibition while also reducing the risks of substance use.

In a legalized system, we could undo the harms of the current system by incorporating some important objectives:

- Economic justice – The current system strongly supports illegal actors and the criminal justice system. A legally regulated market for drugs should support communities that have been most affected by our current approach through jobs, opportunities, and living wages. Taxes on legally sold substances should be directed back into services for those communities.

- Public health – Substances should be treated as an individual and public health matter, not a criminal one. A legal system should proactively work to end the stigma associated with participation in the drug economy and create safe access to substances. Evidence-based education, harm reduction, and treatment services should be widely available and accessible.

- Social justice – Current policies have disproportionately targeted poor, Indigenous, and marginalized communities, as well as people of colour, women, and young people. Legal regulation should actively support undoing the harms of criminalization, including expunging criminal records. The system should work to rebuild relationships between the state and affected communities.

- Environmental justice – A legal system should put environmental safeguards in place around production, packaging, and distribution, and create a sustainable market.

- Trade justice – Canada currently operates in an international system for illegal drug production and trade that creates violence in countries where drugs are produced and sold. A legal system should support a fair global market for products that preserves and protects traditional and cultural production and use of substances.